Why Printed Books Are Better Than Screens for Learning to Read: Q&A

By Alyson Klein — March 15, 2023 3 min read

Students who want to read about dinosaurs, delve into English literature classics, or just immerse themselves in a good story have plenty of options: Traditional paper books, e-readers, audio books, tablets, computer screens, even their phones or smart watches.

When it comes to learning, however, are all these mediums created equal? Which are best for comprehension, and which are best for younger students? And how will the increasing digitization of books reshape reading instruction?

To unpack those questions, Education Week spoke with Maryanne Wolf, the director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. Wolf is also the author of Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World, published in 2018 by Harper Collins.

Is it a good or a bad idea to have students read on a screen versus on a real piece of paper?

The reality is more complex than a nice, neat, tidy binary. If only it were that simple.

The reality is that we have very interesting data that stretches from 3-year-olds all the way through young adulthood, which suggests there are advantages and disadvantages of each medium, depending on the purpose or intention.

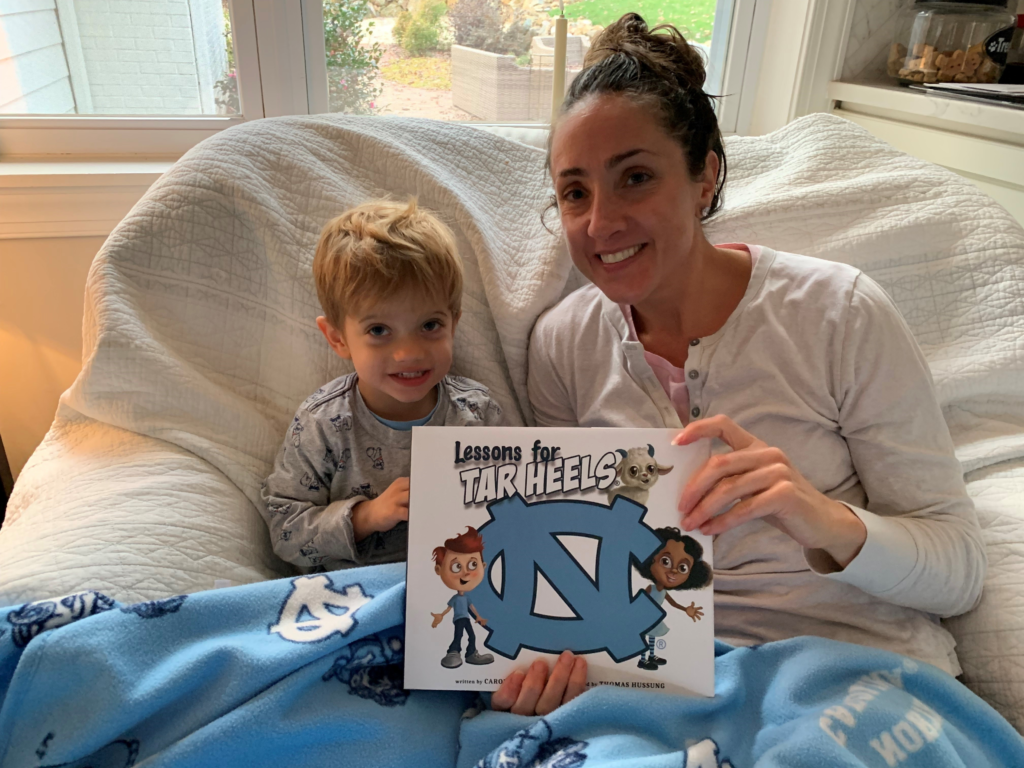

Reading developmentbegins well before any teaching. For young children, physical books are best, audio is second best, and tablet is a clear third. And the reason is that there is a certain double-edged sword here. On the one hand, the tabletis more engaging. On the other hand, it’s a passivity of engagement. It is over-utilizing what we call the novelty reflex that human beings have. This is the last thing we want for child development because we’re wanting them to learn to focus. Instead, they are learning to be distracted.

The most common two words after the child goes off the screen: ‘I’m bored.’ Why? Because they are overstimulated. So between zero and five, the evidence has become quite clear that children’s use of the screen is helping to develop the opposite of what we want in focusing of attention.

Books are really one of the greatest tools for the mind and should never be lost until we are assured that the same processes that were advantaged there are not being diminished by the other mediums.

director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies

When are screens helpful?

You heard me say from the start, this is not a binary, right? And I really am very serious about that.

Print has more advantages for children’s learning than screens. However, children who are struggling, like those with dyslexia or those who have a really limited background knowledge on a subject, you can use digital complementary programs for giving that child practice.

The brain never had a single gene or a single region that was specific for reading. Reading is an invention. And what the brain has is the capacity to make new connections among its genetically programmed parts, like vision and language and aspects and cognition. So what reading does, and that’s why the 0-to-5 period is important, is it takes those regions that had been developing for five years, and it connects them.

We can use digital screeners [diagnostic tests that can be paper or digital] to see what [a student’s] development is like. So we want to see: Do they know their letters? Do they know the sounds? Do they have any idea that the sounds are spelled by letters? What is the vocabulary like? We also want to take a look at processing speed.

So even from the start, digital can be used in excellent ways, as a screener [to get an initial handle on a student’s skill level] and as a form of practice for children.

There are fewer people reading physical books these days. What are the implications of that trend?

The perception of the students is that they’re better readers on the screen. They believe that they’re better on the screen because they’re faster. They are faster, but they are faster because they [are] basically scrolling, word spotting, skimming, scanning. That means we have a need to really hone these deep reading skills in print, and then teach their use on digital screens.

We know that print has advantages because it encourages the time-consuming deep reading processes. But in the future, we’re not going to have people like me. We’re going to have most people who are just digital natives. The question is: how do we get the brain to be a deep, empathic, critical, insightful thinker?

Books are really one of the greatest tools for the mind and should never be lost until we are assured that the same processes that were advantaged there are not being diminished by the other mediums.

Alyson KleinFOLLOW

Assistant Editor, Education Week

Alyson Klein is an assistant editor for Education Week.