One Generation to the Next

From Earl to Tiger to Charlie, how golf is passed down from Woods to Woods

Bob Harig, ESPN Senior Writer

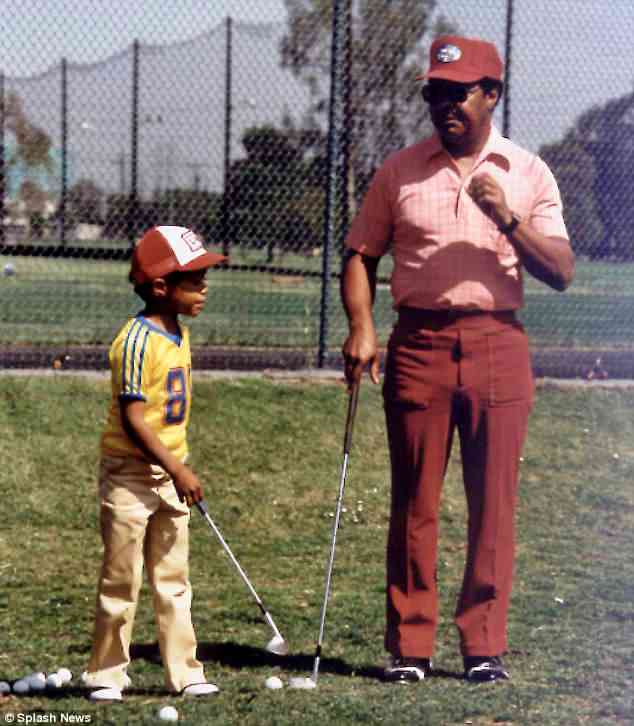

Tiger Woods‘ early prowess as a golfer and the influence his father, Earl, had on his development are legendary. It is the stuff of books and movies, and the 15-time major champion himself has long cited his dad’s encouragement as a big factor in his success.

Earl, an Army veteran, had access to the Navy Golf Course near the family home in Cypress, California, where the two nurtured their bond and where Tiger played a good bit of his early golf.

It wasn’t luxury. Nor did it matter. And Tiger didn’t know any better.

The circumstances are quite different today for Tiger’s son, Charlie, who is set to make his public debut in a golf tournament at this weekend’s PNC Championship, also known as the Father-Son. (The tournament is for major champions and usually their sons.)

Unlike the hardscrabble layout where Tiger grew up, Charlie has been schooled behind private gates, mostly at Tiger’s home club, the Medalist, in Jupiter, Florida. Understandably, Tiger has taken pains to shelter both of his children — Charlie’s sister, Sam, is 13 — from the glare he faced from such a young age.

Perhaps that is why Tiger’s decision to play in the tournament at the Ritz-Carlton Resort in Orlando, Florida, came as a bit of a surprise. Nobody outside of his circle really saw this coming, and yet it speaks to Tiger’s evolution and the joy he sees in watching his son play the game that he is willing to take this on.

When Tiger was 11, things were completely different.

Earl all but guided Tiger from the crib to be a golfer. By the time he was 13, Tiger had appeared on the “Today” show, “Good Morning America,” ESPN and each of the network’s evening news shows, among others.

There is the clip of Tiger on “The Mike Douglas Show” at age 2, putting for a national television audience. Another time he appeared with Bob Hope. Jim Hill, a longtime Los Angeles sports anchor, was one of the first to “interview” Woods when he was barely out of diapers.

Getting Woods to say anything became a big challenge — and foreshadowed the accomplished, famous Tiger. Among Woods’ never-aired responses to Hill was “I have to go poo-poo.”

“He was written up in Golf Digest at age 5,” said Golf Digest contributor Tom Callahan, who wrote “His Father’s Son,” a book about Earl and Tiger that was published in 2010. “Hughes Norton [Tiger’s first agent at IMG] read about him in Golf Digest, and Tiger was a preschooler.

“And the next time he went to California, he took a drive to Cypress and knocked on the door. Tiger was riding a tricycle out front. Earl said to him, ‘Mr. Norton, I think a Black guy who is a good golfer is going to make a hell of a lot of money.’ Norton said, ‘Yes sir, Mr. Woods, that’s why I’m here.'”

Tiger was 5.

At the Navy course, Tiger would put three cherries in his Coke and enjoy a place that had none of the luxuries of country club life, such as showers in the locker room or even air conditioning in the pro shop.

Owned by the Naval Weapons Station at Seal Beach, the Orange County course sat at the end of a regular street behind a sign that read, “U.S. Military Reservation, Naval Golf Course, Authorized Personnel Only.”

It is where Tiger shot 48 for 9 holes — at age 3. It is where he learned to play with the noise of fighter planes taking off and landing from the adjacent Joint Forces Training Base in Los Alamitos. It is where there was a tall elm tree on the sixth hole known as “The Tiger Tree,” which stood more than 300 yards from the tee. Tiger hit it as a teenager. His dad would say he’d be ready for tournaments once he got his tee shots to roll past it. Woods considered Navy his home course until he went to college.

Tiger mirrored Earl’s swing in the garage where the older Woods would hit practice balls. The kid was a natural, as many have pointed out over the years, and the legend grew from there.

Earl was far more gregarious than Tiger ever became, a larger-than-life character who loved the microphone and had no problem touting his son’s ability to any reporter who wanted to ask him questions. In that way, he was the complete opposite of Tiger, who at an early age grew weary of the probing questions and wondered as a young man why he had to deal with them. That carried over into his pro career, and Earl always told him to not give any more than necessary.

That wasn’t Earl, however. He once boasted that Tiger would “do more than any man in history to change the course of humanity,” in a 1996 Sports Illustrated story. “He is the Chosen One. He’ll have the power to impact nations. Not people. Nations. The world is just getting a taste of his power.”

That year, Woods turned pro after winning his third straight U.S. Amateur title. He signed endorsement deals with Nike and Titleist that were worth $60 million over five years. When there was considerable debate about whether Tiger could earn enough money in the seven PGA Tour starts he was granted after turning pro to avoid the year-end qualifying school, he went out and won two of them.

“I saw this happening,” Earl Woods said during a 1996 interview at the Skins Game where Woods was invited on the heels of his quick pro success. “I used to say to the guys when I got out of the service more than 20 years ago, there is going to come a golfer who hits the ball as long as Andy Bean. He’s going to putt like Ben Crenshaw, hit the irons like Johnny Miller. And manage his game and have the mental toughness like Jack Nicklaus.

“In other words, he will have everything. They used to say, ‘Ah, no, nobody is going to come along like that.’ And I would argue. Golf is getting more athletic people all the time. It’s just a matter of time before a superstar chooses golf.”

For all his bluster, Earl — who died in 2006 — was not the type to push too hard, as has often been the unfortunate characterization. Sure, Earl Woods rattled coins in his pocket to try and throw a young Tiger off his game. He called him names and tried to make him uncomfortable. He pointed out the racial epithets he might hear. He might warn him about out of bounds, or hit the brakes really hard on a golf cart, or cough on demand.

While this might have annoyed Tiger, it was meant to embolden him, to strengthen him. Earl knew exactly what he was doing.

But more than anything, Earl gave his son the opportunity, then stepped aside, with Tiger’s mom, Tida, there for support, always taking her son to the various tournaments and rooting him on from afar.

“The notion that he was a product of overbearing parents who orchestrated his life is a fallacy,” John Strege wrote in his 1997 biography of Woods. “They never told him that he had to practice. Often, they had to rein him in and were concerned that golf was too much of an obsession.”

As far as we know, Charlie has no “team” around him at this point other than his dad. But early on, Earl developed the concept of Team Tiger, and it included his first coach, Rudy Duran, and Jay Brunza, a Navy captain and clinical psychologist who often caddied for Tiger but also helped him with the mental side of the game.

In 1982, when Tiger was just 6 years old, he was invited to partake in an exhibition with Sam Snead, the Hall of Famer who held the record for most PGA Tour victories in a career (a record Tiger matched by winning the Zozo Championship in 2019), winning tournaments into his 50s. The event was held at Soboba Springs Country Club, a Southern California desert course, where they would play a two-hole tournament on the 17th and 18th holes.

The 17th was a par-3 with water on the right side, and Woods’ tee shot faded toward it and came to rest barely in the water. “Take it out and hit it again,” Snead told the boy.

Tiger had other ideas, going down into the water to hit. He knocked it on the green and two-putted for a 4. Tiger ended up losing to Sam by a stroke, and afterward, the seven-time major winner offered his autograph. Tiger reciprocated by giving Snead his autograph.

And along the way, Tiger accumulated golf trophies in such abundance the Woods ran out of room for them.

“It got to where it was way beyond what I initially thought,” said Duran, his first teacher. “He was unbelievably good at golf at 5 years old. When I first met him he was 4 ½ and hit some balls on the driving range, I had never seen a kid hit a ball like that. You see parents with their kids, hitting balls, balls going everywhere. But not Tiger.”

And he would get better. Much better. Duran kept working with Tiger until he was 10 years old, and by then he was enough of a presence around the Navy course that some of the longtime patrons got annoyed with this kid — who was so good — having his run of the place.

At right about the age Charlie is now, Earl switched coaches for Tiger to help take him to another level. John Anselmo would guide him until he hooked up with Butch Harmon at age 16.

And that is where another difference comes into play: With Tiger in charge, it seems that only one coach will ever be necessary, the one who will be playing with Charlie this weekend.