North Carolina education leaders discuss cellphone use in schools

October 21, 2024, By Laura Browne

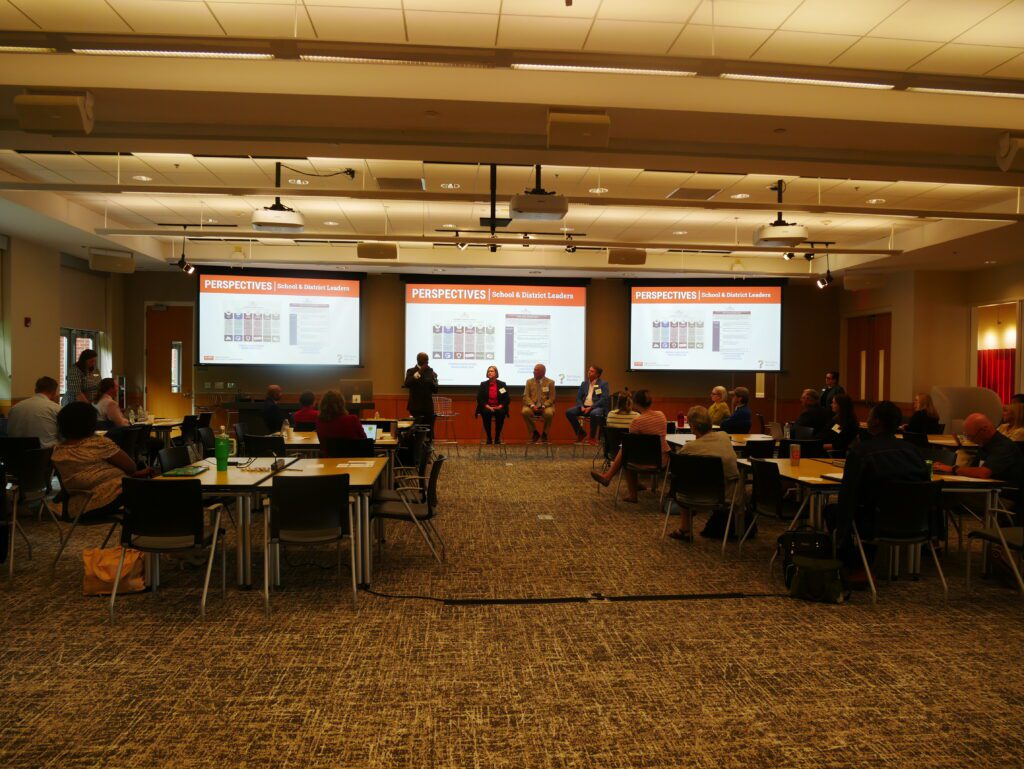

Educators, elected officials, and other stakeholders gathered in Raleigh last week to discuss diverse viewpoints regarding the use of cellphones in schools.

The convening, hosted by the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation on Sept. 12, focused on making policies to regulate phone use rather than a total ban.

“When we ban things, we create groups,” said state Superintendent Catherine Truitt. “We create groups who are in favor and those who oppose, and then we often attach some sort of morality to that… This is why bans are so problematic. This needs to not be about banning cellphones. It needs to be about creating policies that are right for students and their families and teachers, so that our students can thrive.”

According to the Pew Research Center, about one-third of K-12 teachers in public schools consider distractions from cellphones a major problem in the classroom, with another 20% calling it a minor problem. Nearly three-fourths of high school teachers (72%) say cellphone use is a major problem, according to the data.

Though phones are often seen as distracting, many parents and guardians want their students to be able to have phones in schools, primarily to reach them in an emergency situation.

Lauren Gendill, policy analyst with the National Conference of State Legislatures, said at least 22 states have proposed legislation related to cellphone use in schools, and eight states have enacted such legislation since 2023. North Carolina is not one of them — though a bipartisan bill was filed in May that would require a study be done on cellphone policies in school districts.

Last week’s conference featured a variety of perspectives, including psychologists, students, educators, policy analysts, and others. Speakers and panelists talked about how cellphones can provide learning opportunities and other social and educational benefits for students, but can also distract students and bring challenges to mental health and development.

Enloe Magnet High School student Lucy Ashburn spoke at the conference to offer a student perspective on the issue. Ashburn said her teachers often ask students to use their phones during class for tasks like completing Google Forms or playing Kahoot!, a game-based quiz platform.

Ashburn said that having access to cellphones in school is often beneficial to students, as it provides them the ability to contact parents if needed, but phones can also cause distractions for both the student using the device and others around them.

“I feel like that’s good to be able to have something in your pocket,” Ashburn said. “You can text your mom, you can text your dad if you need something at school, and that’s helpful technology. But also, the constant feeling like, ‘Oh, did someone text me? Is my friend texting me?’ That’s always there, because you always have it in your pocket and in class. That can be hard to experience trying to stay engaged.”

Mitch Prinstein, chief science officer of the American Psychological Association and John Van Seters Distinguished Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at UNC-Chapel Hill, said young students lack the ability to effectively task shift, and access to phones can create additional obstacles to a student’s focus.

“If they have access to a device, including their own personal device, and they’re able to do that during school, it is probably going to be related to distraction, which is probably going to affect their school performance,” Prinstein said.

The conference at the Friday Institute featured several different perspectives on cellphone use in schools. Laura Browne/EdNC

Opportunity for education

Some speakers said that cellphone use presents a learning opportunity in schools.

Educators can teach students through conversations about effective technology use that they may not receive at home, said Anne Ottenbreit-Leftwich, the Barbara B. Jacobs Chair in Education and Technology at Indiana University-Bloomington.

“If we’re producing students that aren’t able to use those technologies to express themselves, they’re not going to be as competitive as maybe other states that do have that capability,” Ottenbreit-Leftwich said.

Cultural anthropologist Mimi Ito said cellphone bans can also lead to inequity, as bans are often unequally carried out, with bans being applied more rigorously in lower-income public schools.

This means that wealthier students, who may already have greater access to technology, are more likely to have a better understanding of how to effectively engage with their devices than their lower-income peers, Ito said.

“There’s a tendency for the rich to get richer in terms of the deployment of technology,” Ito said.

Ito said though different kinds of technology have emerged and evolved over the past decades, a consistent trend is adults reacting with fear or restrictive impulses when youth engage in technology they didn’t have access to growing up.

“This is a consistent pattern that the stigmatization and demonization of technology in the hands of young people have created a new set of intergenerational tensions,” Ito said.