What Does College Football Have to Do With College?

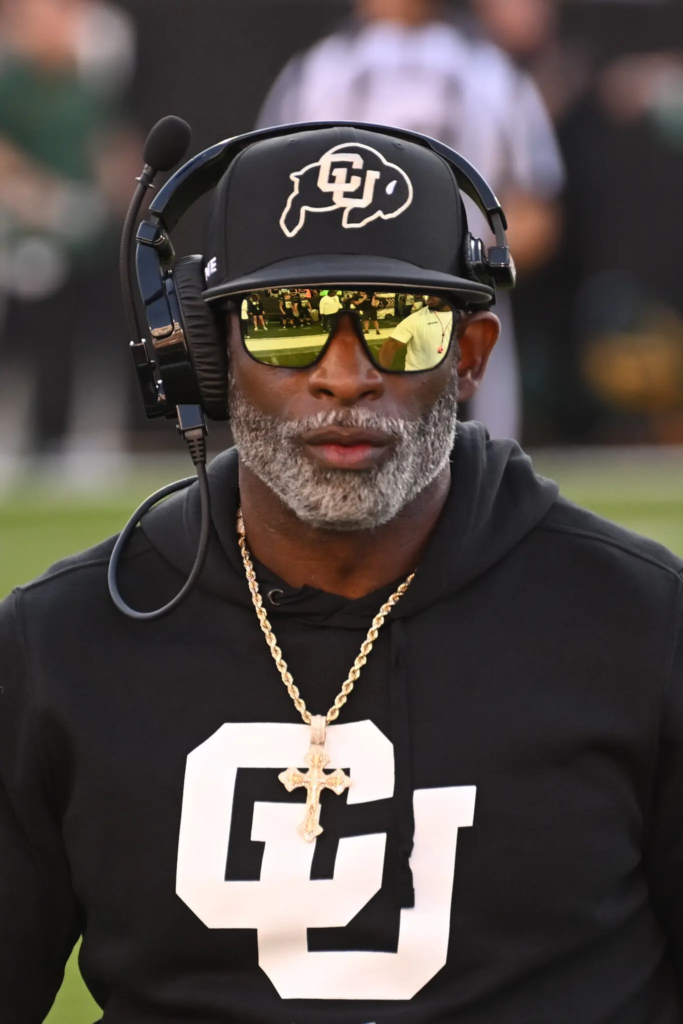

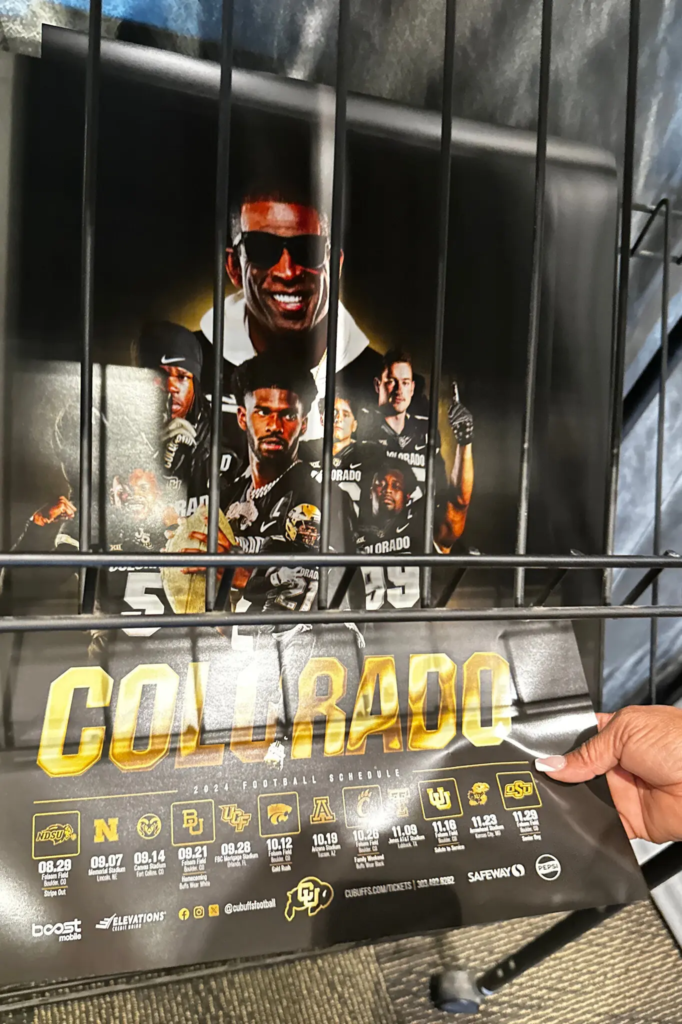

The question isn’t new. But seismic changes to college sports, embraced by Coach Deion Sanders and his University of Colorado Buffaloes, have made it more relevant than ever.

By John Branch

Photographs and Video by Mark Makela, published Oct. 4, 2024

Students poured onto the field. In the dry cocoon of the press box, cynicism washed away. I laughed. That’s when I came closest to answering the question that I had come to ask:

What is the point of college football these days?

For more than a year, from a distance, I had watched Colorado absorb the “Prime Effect” of Coach Deion Sanders, the famous former football player nicknamed Prime Time. He has injected the place with enthusiasm and brought it fresh attention. Friends and family have been so gaga that I worry for their senses.

Colorado is my alma mater. I have attended games in Boulder since I was a kid in the 1970s. But it’s 2024. I am a reporter. I have questions.

Mainly, what does college football have to do with college?

This is not about Sanders, but about the rest of us. Even if we dismiss the debate over playing brain-breaking games at institutions tasked with making people smarter (which we collectively do, it seems), does a multibillion-dollar sports enterprise, attached to American universities, make any sense?

These questions, asked of friends before Colorado’s homecoming game, were met with quizzical looks that said, “You OK?”

My questions aren’t new, but renewed. We are witnessing the biggest upheaval in college sports history. Some annual college athletic budgets surge past $200 million. Television contracts balloon into the billions. Conference alliances are erased and redrawn as with an Etch A Sketch. Players transfer from school to school, mercenaries open to the highest bidders. The organizational scaffolding of the NCAA, fussy and obsolete, is in a useless pile.

An expanded playoff is coming at the end of this season. Tennessee recently announced a 10 percent “talent fee” on ticket prices to help pay players, part of a nationwide fund-raising scramble for stars. There is talk of an enormous superleague, tentatively called the College Student Football League.

None of it seems to be done in the interest of education. Yet the bands play on, stadiums fill each Saturday and no one with a cheerleader’s megaphone seems to question what is happening.

Have we sane-washed college football?

Nowhere is the dynamic playing out as it is at Colorado. An hour before the season opener in late August, I sat on a bench near Folsom Field. It remains a modest place, built 100 years ago to blend into a campus routinely named one of the most beautiful in the country. The stadium feels like a time capsule, if you ignore the recent architectural appendages — football offices and meeting rooms, skyboxes, grand locker rooms and training facilities, an indoor practice facility — generally inaccessible to most tuition-paying students.

But Folsom Field has something new for everyone this season — a huge video scoreboard, mounted high on the south wall, projecting images inside the stadium and out. To fans arriving for the season opener, it displayed a Nike advertisement featuring the star quarterback Shedeur Sanders, the coach’s son.

He drives a Rolls-Royce and earns more than $5 million in sponsorship deals, according to estimates by On3. Last April, near the end of his third semester on campus, Sanders attended an in-person class for the first time. It was filmed for his social media accounts.

Kickoff approached, and I watched as the band and the cheerleaders marched by. Drunk college students and gray-haired fans wearing Prime merchandise and Colorado logos were gleefully sucked into the communal embrace of the stadium, faces aglow in the evening light.

“Here … comes … Ralphie!” the public-address announcer shouted as the live, half-ton mascot led a team of handlers in an arc on the field, part of Colorado’s pregame tradition.

It was intoxicating. But is college football simply a dose of cotton candy — good for a sugar high but bad for the system?

A Family Tradition

There’s a time-warp element to college football, key to its appeal. It’s built in nostalgia, tradition, a sense of place and a collective experience — including academics. Jerry Seinfeld says that fans just root for clothes, but something about college sports feels more personal. The clothes smell of history and belonging.

My family had Colorado season tickets when I was a kid. We squeezed into Section 104 and mostly watched the Buffaloes lose. I sat with Dad as he listened to the play-by-play through an earpiece strung to his transistor radio. In the fourth quarter, I’d scramble through the emptying bleachers collecting sleeves of souvenir plastic cups.

And then I went to Colorado. My sophomore year, the Buffaloes upset Nebraska. We were transfixed — faces painted, fueled by beer, our weekend moods rising and falling on the fate of the Buffs. After graduation, I became a season-ticket holder, cheering them toward a national championship. Ask me about the Fifth Down.

I returned to campus for graduate school, gave up the tickets and became a sports reporter. My fandom evaporated, as it does for journalists, with remarkable ease.

I haven’t lived in Colorado for two decades, during which the Buffaloes have had 16 losing seasons. That didn’t bother me. As I got older, if I rooted for anything, it was for Colorado to be above caring about winning football games.

Then, at the end of 2022, Colorado hired Sanders. The jolt was the athletic version of defibrillating a moribund patient with electric paddles. Sanders overhauled the program in ways no coach, anywhere, had done. He unapologetically chased out scores of scholarship players from the previous regime. He brought new talent, including Shedeur as the starting quarterback. Another son, Shilo, is a starting safety. A third, Deion Jr., follows his father with a camera and oversees the social media coverage of all things Prime.

Merchandise sales surged. The spring scrimmage, usually a yawn of an afterthought at Colorado, was packed. The team sold out all six home games for the first time. Donations to the Buff Club, the fund-raising arm of Colorado athletics, set a school record.

Sanders brought positive energy and a nowhere-I’d-rather-be vibe. He infused Boulder, a wealthy and overwhelmingly white place, with a welcome dose of Black culture. Application numbers spiked, including from students of color. Pregame shows camped out in Boulder. Celebrities came to practices and games. Sanders was the focus of a “60 Minutes” segment and then was Sports Illustrated’s Sportsperson of the Year.

Colorado was swept up in the “Prime Effect.” Stories were written about all the positive boosts, especially “attention” and “money.”

Now would be a good time for this reminder: Big-time college athletic departments are generally disconnected, financially, from the rest of the university. While football revenue can help subsidize other sports, money from athletics rarely flows to the educational side; it is often the opposite.

Colorado students pay a mandatory “athletic fee” ($28.50 a semester) to help fund sports. They can pay $200 more if they want tickets to games. In 2023, Colorado had a $136 million athletic budget and lost nearly $10 million. Most major universities subsidize athletics, not the other way around.

I went to see Doug Looney the day before the season opener. He was raised in Boulder, graduated from Colorado and spent 22 years at Sports Illustrated, mostly covering college football. He taught journalism at Colorado. I was one of his students.

“The only rules in college football today are inside the lines,” Looney said. It might have been hyperbole, but not by much.

He carried a printout of the university’s mission statement, where there is no mention of sports.

“Football can be a heck of a lot of fun, and there will be a lot of excitement over there tomorrow,” Looney said. “It’s not all bad. If fun and excitement weren’t a big deal, what would Taylor Swift be doing? It’s just gotten out of proportion in college football. And certainly at Colorado.”

I mentioned that I had watched the Amazon docuseries “Coach Prime.” It was produced, in part, by Sanders’s business partner and agent. Over six episodes, no mention was made of anything related to schoolwork.

We laughed at how athletics and academics can’t even agree on math or geography. This football season, the Big Ten Conference has 18 teams, the Big 12 has 16 and the Pac-12 has two, in part because California and Stanford, both a quick drive from the Pacific Ocean, left for the Atlantic Coast Conference, where the money was better.

Looney pondered where college football would be in 10 years. What’s the goal of this game?

“Bigger, bigger, bigger,” he said. “The age-old question is, Is bigger better? I think the answer, routinely, is no.”

Last spring, Colorado offered a course called “Prime Time: Public Performance and Leadership.” It was created by Rick Stevens, an associate professor of media studies.

“Every day is a case study,” Stevens said, noting that Sanders, who made several appearances in class, has always been a pioneer in image making. Now he is pulling the University of Colorado wagon train along with him, blazing a trail to, well, somewhere.

“Their sense of global participation and surveillance and awareness, all of that is on the rise,” Stevens said of Colorado students. It is all “net positive,” he said.

This fall, Stevens teaches a course called Sports-Media Complex. On the day of the season opener against North Dakota State, he lectured about the historical ties between religion and sports. He explained the humble origins of college athletics, rooted in physical education and aimed at honing the body as well as the mind. He spoke of tradition and ritual.

Raised hands showed that almost all of the students in class eagerly planned to attend that night’s game. Students were assigned by the athletic department to wear white.

“You are participating in the construction of a media image tonight,” Stevens pointed out.

It’s all marketing, isn’t it? If we’re being blunt, a primary function of college athletics is to entertain and build loyalty to a brand. Students become alumni; alumni become donors. Fans get hooked and feed the system. But what’s the system? What’s the goal? That’s where it becomes hazy.

For more than two weeks, I requested a few minutes, in person or on the phone, with Colorado athletic director Rick George, who hired Sanders. I said I mostly wanted to ask one simple-sounding question: Why does the University of Colorado have a football team?

George declined to be interviewed. But athletic directors and university presidents often invoke an axiom: The athletic department is the front porch of a university. It’s what everyone sees.

B.G. Brooks spent nearly 30 years covering University of Colorado sports, mostly as a Denver newspaper reporter and then for the athletic department. Now retired, he and his wife watched the opener from seats under that new scoreboard.

“Athletics have gone further than the front porch,” Brooks said. “They’ve gone from the front porch through the foyer, almost to the living room. They’ve stuck their head into every part of the university, at least at C.U. It’s hard for me to take.”

Prime’s Primacy

I was back in Boulder for the week of the homecoming game against Baylor. I spoke to 50 students in a journalism class. I asked if any of them had reservations about the Prime Effect. No one did. They all planned to be at Saturday’s game.

After class, I met with professor Jamie Skerski, a former college softball player. She teaches a course called Communication, Culture and Sport.

“I teach in this brand-new building, and I needed some extra desks because I had more students than desks,” she said. “It took three weeks to get them. But there were Coach Prime sweatshirts in the bookstore within 48 hours of his hiring. It’s kind of reflective of our values.”

I asked the direct question: Should universities be in the business of football?

“We need to rethink the prominence of football just on a safety level,” she said. “And we would be mistaken to not seriously question the way that football either doesn’t connect to, or actually contradicts, the academic mission.”

A web of court cases, mostly aimed at improving athlete rights, have created changes like the ability to collect on name, image and likeness (N.I.L.). College athletes, but especially men, and especially football players, are cashing in on sponsorship deals as N.I.L. collectives, loosely associated to universities but run mostly by boosters, raise money to lure talent. Skerski believes that schools squandered a chance to rethink priorities of all sorts: funding models and gender equity, mental health and travel limits. Was anyone making decisions, she wondered, who wasn’t thinking just about the bottom line?

She noted that most American professional sports, like the N.F.L., were anchored in socialist tenets — revenue sharing, salary caps and the tradition of giving the worst teams the first pick in the draft. College sports, more than ever, are wildly capitalistic and feel a bit lawless, she said.

“All of these changes have cemented football’s dominance rather than questioning it,” Skerski said.

None of this was on the minds of fans as they filed into the homecoming game. Ralphie ran, the band played, alumni solemnly sang the school’s alma mater. The student sections throbbed throughout a taut game with Baylor.

Rain fell. Colorado looked certain to lose. But on the last play of regulation, from the 43-yard line, Shedeur Sanders scrambled to his left and heaved a pass to the goal line. It landed in the hands of a diving Colorado receiver.

Fans went berserk. In overtime, Colorado forced a fumble at the goal line and won, 38-31. Thousands of students charged the field, wearing white, as directed.

I watched from the press box, slack-jawed, having thought I’d seen everything at Folsom Field. Below me, down in familiar Section 104, my wife and dozens of friends were part of the soaked, surprised, joyous chorus of Colorado fans.

We reunited in the old field house, where I used to warm up during cold game days with my dad, where they still have trough urinals, where I spent my first day as a college student, standing in line to register for classes.

With thousands of others, in the rain, we slipped happily through the dark shadows of campus. Everyone was having so much fun — a shared experience, already being retold and relived.

Colorado is now 4-1. On Wednesday, The Onion, the satirical news site, posted a college football headline.

“Deion Sanders Admits He Has No Idea What School Colorado Buffaloes Play For,” it read.